Black: Indelible and Enigmatic

Chalk black. Iron black. Warm Mars black. Cool Zinc black. Ebony and obsidian black. Bone black. Lamp black. Carbon black (car tires have six pounds of carbon black in them). Flat, thin or thick black. Shallow black. Deep black. Now there’s an even blacker black, called Vantablack, a substance that absorbs up to 99.6% of radiation in the visible spectrum. “It is a structural color, like peacock feathers, beetles’ epicuticles and the blue of the sky,” said Dr. Narayan Khandekar, Director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies and the Center for the Technical Study of Modern Art at Harvard Art Museums. “It is so black, so light absorbing, that even when you know there is a form in there it is impossible to make out, nothing to hint at three dimensionality. It’s like staring into a black hole.”

All-out black. Black without reference. Without dimension. Nothing to compare it to. It is itself.

It’s not as if artists have to use black to create dimension and contrast. A blend of Aureolin (Cobalt Yellow), Rose Madder, and Cobalt Blue make a soft black. A bolder black is made by mixing Winsor Yellow, Permanent Alizarin Crimson and Phthalo Blue. Magenta and cyan also make black. In fact, any red and blue will work. “Black is a force…comparable to that of a double-bass as a solo instrument…it permits me to color my blacks like my whites, to animate my surfaces and gives the image the interior rhythm that corresponds to the expression of the author,” said Matisse.

Black asserts authority and power. Just look at the paintings of Richard Serra or Franz Kline—slashes of black against white. Do we look at the white? No, the black is indelible and immediate. A statement. On. Point.

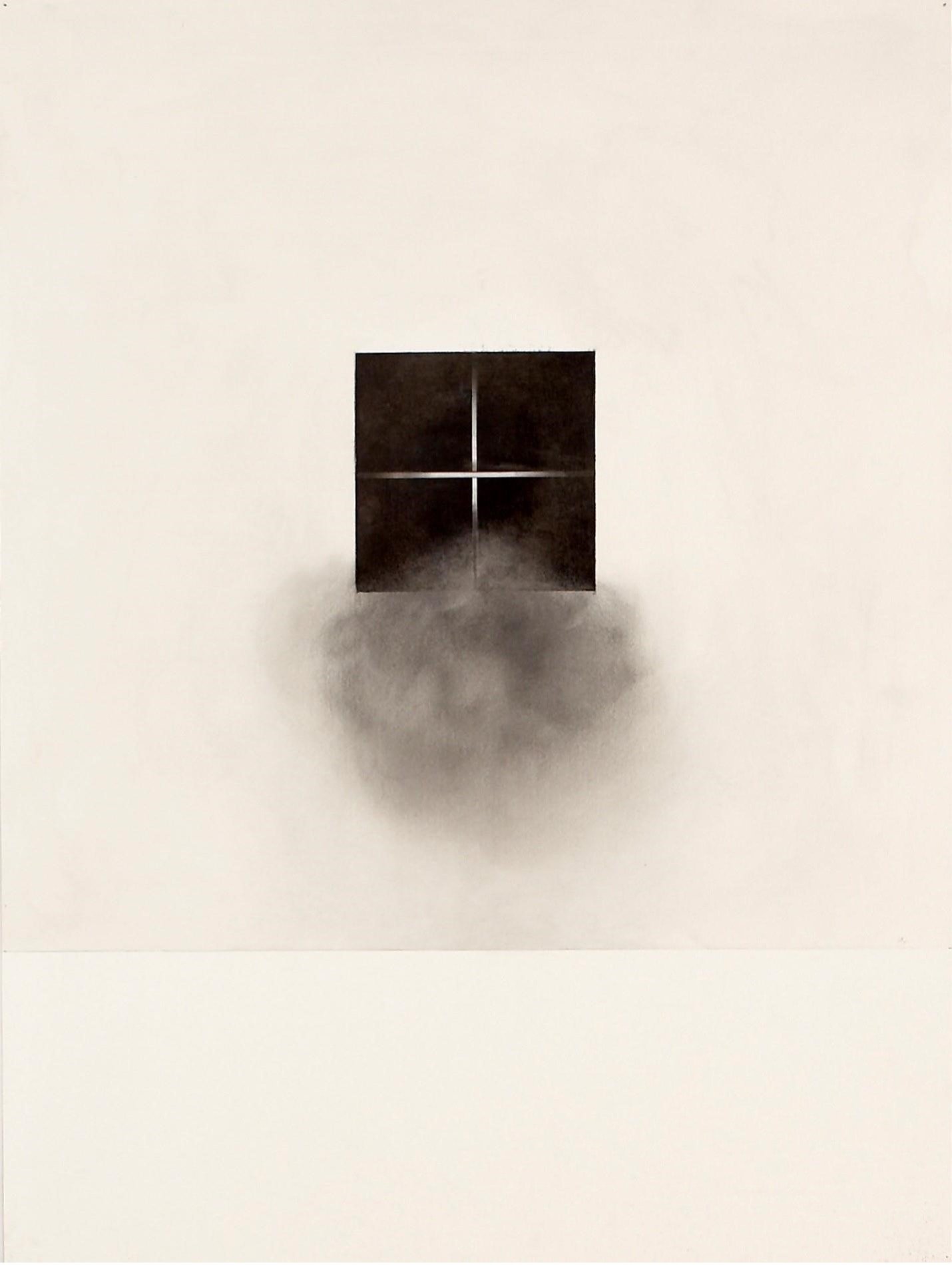

Gerald Auten said this about his buffed graphite on paper drawings (pictured): “Is a deep black square an object or an opening? Sometimes you can get a surface so deep, rich and black that it begins to contain an immense amount of space and light. Your perception begins to equivocate, reading it as both object and void.”

Black pigments were abundant in Paleolithic cave paintings. This deep, carbon black was made from charred wood, bone and antlers. Ancient Greek and Roman painters used lampblack, especially for small surfaces. Particularly valued by the Romans was the black derived from vines and oak galls. But in the late 1400s, Leonardo da Vinci claimed that black was not truly a color. Adding to that, in 1665 Isaac Newton invented the color wheel and left out black (and white), considering them “noncolors.”

Graphite was discovered in Borrowdale, England in 1564. This mineral made a darker mark than lead but it was so soft and brittle, it had to be encased in hollowed-out wooden sticks.

The first mass-produced pencil was developed in 1662, in Nuremberg, Germany. America’s beloved Faber-Castell became a flourishing pencil manufacturer in 1761. Aniline black, an organic compound extracted from coal tar producing a dark viscous substance, was discovered in 1880. This black became one of the first synthetic dyes.

In the early 20th century, artists began to use black defiantly and eloquently. Picasso’s powerful mural, Guernica, was painted in black and white. Jackson Pollack’s enamel black on canvas in the early 1950s, along with Mark Rothko’s thinly applied black squares mixed with blue, are works pulsing with energy and depth. Joan Mitchell’s Black Drawings (1964-1967), are a series of swirling charcoal drawings with flashes of sepia pastel on soft, textured handmade paper.

Today, along with Gerald Auten’s powdered graphite drawings in which he uses WD40 as a medium, there are any numbers of artists working in black. Christopher Wool and Robert Longo are well known for the use of black in their work. James Turrell's dark chamber, Hind Sight (Dark Space) 1984, currently at MASS MoCA, is an experience the artist describes as “seeing yourself see.” The brilliant sculptors Eva Rothschild and Stina Köhnke use cast iron, steel, plated leather, and fabric to create their monoliths of black. Susan G. Scott’s oil on canvas, The World is Round (2017) is a proud, light-filled landscape in black and white, testimony that black can convey nature’s vibrancy beautifully.

The Dark Ages, black holes, night, death; black is enigmatic. So like our own natures.

Note: Harvard Art Museum has a sample of Vantablack on display on the 4th floor so visitors can experience it firsthand.

Dian Parker is a freelance writer, published in a number of literary journals and magazines. She is the curator of White River Gallery in Vermont and an oil painter.

Gerald Auten, Auten, 2006, graphite on paper, 24 x 18” Photo by Dian Parker